2024 Tax Strategy Playbook

Download the Tax Strategy Playbook for tax insights and opportunities that could impact your organization in 2024.

Baker Tilly’s inaugural Tax Strategy Playbook discusses the outlook for the new year’s tax policy landscape, outlines how current tax policy impacts your business, and discusses opportunities for tax planning and mitigating inherent risks. We delve into various areas within federal, global and state and local tax.

Explore our comprehensive guide on federal tax policies for pass-through entities like S corporations and partnerships. Navigate complexities with ease.

Without further congressional action, many of the federal tax provisions enacted under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 that impact pass-through entities and their owners are scheduled to sunset at the end of 2025.

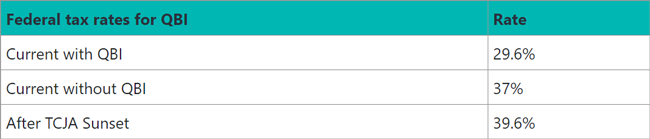

Individual tax rates will revert to the pre-TCJA rates with a top marginal federal income tax rate of 39.6% (up from 37% under TCJA). The rate increase for business income is likely to be even more significant, as the qualified business income (QBI) deduction will also sunset. The QBI deduction, which allows for a deduction equal to 20% of certain categories of business income, effectively reduces top tax rates for qualifying business income from 37% to 29.6%.

There are strategies taxpayers can implement to take advantage of current rates. Taxpayers would be well-served to take a fresh look at existing methods of accounting and elections and thoughtfully structuring upcoming transactions.

Absent any legislative developments, the corporate federal income tax is permanently set at 21%. When the QBI deduction is no longer available, depending on the particular facts and circumstances, taxpayers may find that operating in a corporate structure could lead to an overall reduction in tax burden. As with any major change, taxpayers should carefully model the alternatives and consider the prospect of potential future legislation before making any adjustments.

Finally, in response to the state and local tax (SALT) limitation on individual itemized deductions, many states enacted elective pass-through entity tax (PTET) regimes. The PTET effectively shifts the primary burden of state income tax from the owner to the pass-through entity itself. If the SALT cap sunsets after 2025, the benefits of making PTET elections will shift for some taxpayers, though not in a simple way as SALT deductions are one of the most common items that shift a taxpayer into owing alternative minimum tax. Taxpayers who have previously elected into a PTET regime will need to take a fresh look at PTET elections to determine whether the benefit of the PTET regime continues to outweigh its cost.

As we await any congressional action extending or altering the TCJA’s expiring provisions, taxpayers should begin to consult with their advisors about planning opportunities for current and future tax years.

The Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2015 established the centralized partnership audit regime (CPAR). This new system changed how partnerships adjust their prior year tax returns through an exam or tax return amendment. Under CPAR, partnerships must modify their tax returns through an administrative adjustment request (AAR) instead of an amended return.

The calculation of an understatement of tax (called an imputed underpayment or IU) can be severe as it considers most numerical items reported on the partnership’s tax return (including Schedule K-1) and applies the highest marginal tax rate related to any adjustments for those items. This includes items not typically associated with determining taxable income (e.g., allocation of liabilities or tax basis). While the taxpayer does have the ability to demonstrate that the imputed underpayment should be reduced based on the partners’ tax profiles, the CPAR shifts this burden to the partnership.

CPAR has also changed the relationship between partnerships and their partners. For instance, when confronted with a positive adjustment, the partnership may have the option of either paying the imputed underpayment discussed above or pushing the adjustment out to the partners as of the reviewed year. In the former case, the burden of the tax liability effectively rests with the current partners. In the latter case, the burden of the tax liability rests with the partners as of the reviewed year, which could include former partners. This puts both the partnership and the partners in a precarious and potentially adversarial situation.

CPAR fundamentally changed the examination and modification of partnership tax returns. Due to the complexity in its requirements and procedures, partnerships and partners should proactively consider address, and document within the partnership agreement issues that can arise under CPAR to mitigate exposure.

When the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 passed, it was the largest tax legislation in decades. Among the many changes made by the TJCA was a limitation to state and local tax (SALT) deductions for individuals; for tax years beginning after December 31, 2017 and before January 1, 2026. This provision limits individual taxpayers to a maximum itemized deduction of $10,000 for all state and local taxes paid. It is not uncommon for individual taxpayers to meet the SALT limitation based solely on residential real estate taxes paid; this leaves taxpayers without any tax benefit for their state and local income taxes paid.

In the years following the TJCA’s enactment, most states with an income tax have developed a workaround that allows pass-through entities (PTEs) to elect to pay state income tax at the entity level. It is referred to as the pass-through entity tax (PTET). When elected, PTE owners typically either exclude the income entirely for state income tax purposes or report the income and a corresponding credit for the tax paid at the entity level. This deduction decreases the PTE’s federal taxable income, which results in less income reported and, thus, a lower tax liability for the PTE’s owners.

While the PTET creates a tax benefit for the owners of most PTEs, it is not without its costs and challenges. In addition, there can be inequities in the efficacy of the PTE for different owners of the same entity, depending on the individual circumstances of each owner; these can be particularly challenging in S corporations.

Despite the challenges associated with electing the PTET, it can be a very effective tax reduction tool.

Consider the following example:

PTEs should examine the effects of making a PTET election on their owners and run a cost/benefit analysis with their advisors before making the election.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 limited the state and local tax (SALT) deductions for individuals. In reaction to this limitation, many states have enacted a pass-through entity tax (PTET) to allow partnerships and S corporations, rather than the individuals, to claim a deduction for business income taxes.

There has been much uncertainty surrounding the timing of the deduction of accrued PTET at the entity level. For overall cash method taxpayers, the answer is straightforward — deductions are generally allowable in the tax year in which they are paid; however, prepayments are only deductible if there is a legal obligation for prepayment.

Accrual basis taxpayers face much greater uncertainty surrounding the timing of the PTET deduction. In order to claim the deduction in the current year, it must be fixed and determinable at year-end and economic performance must have also occurred. For taxes, economic performance generally occurs when the taxes are paid. One exception relates to the recurring item exception which provides that, if the liability is fixed and determinable by year-end, taxpayers can meet the economic performance requirement (i.e., pay the tax) by the earlier of the date the federal tax return is filed, or the 15th day of the 9th month after the close of the taxable year.

An issue arises related to states where the PTET election can only be made after year-end, at the time the state tax return is filed. In this case, there is uncertainty as to whether the PTET liability can be considered fixed as of year-end, as the entity hasn’t and is unable to commit to filing a PTET return. Taxpayers should work with their advisors to consider what steps can be taken to demonstrate their intent to elect PTET by year-end. There is no one-size-fits-all approach; each business will need a facts-and-circumstances determination and should maintain thorough documentation that clearly demonstrates their intent, should they take this approach.

It's important to note that accrual taxpayers may have to file an accounting method change or an amended return or administrative adjustment request (AAR) to accelerate deductions that had previously been deducted when paid. Taxpayers should evaluate their current methods to determine the required procedures to implement any changes surrounding the timing of PTET deductions.

As businesses grapple with the many factors putting pressure on their bottom lines, the excess business loss (EBL) limitation is affecting more taxpayers. This limitation restricts the amount of trade or business losses that noncorporate taxpayers can utilize to offset nonbusiness income, leading some taxpayers with an overall economic loss to report and pay tax on net positive taxable income. Any losses disallowed under the EBL provision are converted into net operating losses (NOLs) for use in subsequent years. Currently, the EBL provision is effective for the 2021 through 2028 tax years.

Planning for the deductibility of noncorporate losses is critical, as the EBL limitation can create a significant disparity between economic and taxable income, further constraining businesses owners experiencing overall economic losses. Planning to minimize taxable income with EBL often centers around timing and structure.

The fate of the EBL limitation beyond the 2028 tax year is currently unknown. Both Democrats and Republicans have discussed plans for possible extensions of the limitation. Furthermore, some Democrats have proposed making the provision more stringent by subjecting disallowed losses to EBL retesting in subsequent years, rather than converting them into NOLs.

Surging inflation and interest rates resulted in significant challenges for many enterprises in 2023. This economic environment will likely lead to an increasing number of businesses producing a net loss in 2023. While relief in the form of deducting these net losses against other sources of taxable income is generally available, a taxpayer must run the gamut of various limitations to ultimately yield the benefit. While some limitations have existed for decades, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017added more limitations to this ever-growing list: the excess business loss (EBL) rules and revisions to the net operating loss (NOL) rules.

The EBL rules, as discussed in greater detail in “Planning for noncorporate business losses,” apply to noncorporate taxpayers only and limit the business deductions taxpayers can claim in excess of business income. Any losses suspended under the EBL rules carry forward to the succeeding taxable year as an NOL.

Prior to the TCJA, NOLs could generally be carried back two taxable years, carried forward for twenty taxable years and could offset up to 100% of taxable income. TCJA removed the two-year carryback provision, made the carryforward period indefinite and limited the NOL deduction to an offset of 80% of taxable income.

As a result of the interplay of the EBL and revised NOL rules, timing of business losses has taken on a new level of importance in maximizing the deductibility of business losses. With proactive planning, taxpayers and their advisors are frequently able to align the timing of income or deductions — whether by adopting or changing accounting methods, utilizing various capitalization provisions, making elections or otherwise — to most effectively utilize business losses. When confronted with EBL and NOL limitations, taxpayers and their advisors should carefully consider and model their specific facts and be prepared to think outside the box to achieve the best possible result.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 introduced a myriad of new provisions to applicable to tax law. One of those provisions limits the deductibility of business interest expense.

Prior to the TJCA, business interest expense was limited by various rules but generally was deductible when paid or accrued. The TCJA created a limitation on the deduction of business interest expense that restricts a taxpayer’s ability to claim the deduction at 30% of the taxpayer’s adjusted taxable income (ATI). This calculation has become increasingly restrictive over the last several years as the limit decreased from 50% to 30% and the number ATI is, as of 2022, based on earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) rather than the previous earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA).

Any interest expense that is not deducted by the partnership is carried forward by the partners until the partnership produces income in excess of the amount needed in any given year to deduct all the current year business interest expense or the partner disposes of its partnership interest (which includes the partnership liquidating).

In the final year of a partnership, or upon a partner disposing of their interest in the partnership, any excess business interest expense carryforward that has not been utilized is added to the basis of the partners’ partnership interests. The result is both a continued deferral of excess interest expense until the partner’s final year in the partnership and a change in the expense’s character from an ordinary deduction to a less favorable capital loss.

In a scenario where a partnership is selling its business, there are tax planning strategies that will result in better tax treatment of the excess business interest expense carryforwards. For example, it may be advantageous to sell assets of the partnership to generate excess income in the final year in order free up some or all the carryforwards; this strategy can preserve the ordinary deduction of interest expense and result in increased after tax cash flow. It’s important to consult with a trusted tax advisor for a comprehensive look at the consequences of any significant transactions prior to structuring or executing.

One of the fundamental principles of partnership tax is that allocations of income, loss, etc. must be consistent with the underlying business deal between the partners. In other words, tax must follow the economics. The economics of the business arrangement are documented in the partnership agreement and tracked in the partners’ capital accounts (think of the capital accounts as an “economic scoreboard”).

Partnerships are extremely flexible and can accommodate a wide range of businesses and economic situations. The cost of this flexibility, however, is exceptionally complex tax rules. Unfortunately, this combination sometimes leads to a disconnect between the intent of the parties and how the deal is documented. The partnership agreement is a contract, so when it comes time to prepare the tax return, the agreement controls, even if the result is not what the partners intended or expected.

Partnership allocation models come in two basic flavors. Traditional “layer cake” or “safe harbor” agreements are governed by a complex set of tax regulations and require careful drafting to ensure that the income, loss, etc. allocation provisions are consistent with the cash distribution provisions. “Target capital” agreements allocate income, loss, etc. so that each partner’s ending capital account in any given year equals, as closely as possible, the distribution each partner would receive if the company was liquidated.

Regardless of your allocation method, the partnership agreement should not be gathering dust in a drawer — it’s important to perform regular checkups whenever business conditions change. Allocations should be stress tested for different financial results (what if there’s a loss instead of income?), potential transactions, ownership changes, etc. to ensure that the results match the intent of the partners. If the results are not what the partners expect, the agreement should be amended before the end of the year (or by March 15th of the following year at the latest).

The IRS introduced Schedules K-2 and K-3 beginning with tax year 2021. The goals were to provide standardized reporting to assist pass-through entities (PTEs) in providing owners with the information necessary to complete their tax returns with respect to their international tax obligations and to allow the IRS to verify compliance more efficiently.

Subject to limited exceptions, all PTEs that have what the IRS refers to as “items of international tax relevance” must complete the applicable parts of Schedules K-2 and K-3. On its face, it may seem that a U.S. PTE with only U.S. operations and U.S. owners would not come within the scope of the filing requirements; however, that’s not necessarily case. The scope of what encompasses items of international tax relevance is extremely broad, and the exceptions to filing Schedules K-2 and K-3 are limited in nature. Under the domestic filing exception, PTEs with only certain types of U.S. owners and no or limited foreign activity may be able to avoid the filing requirements. Other potential exceptions exist with respect to specific parts of the Schedule K-2 and K-3, but do not except the overall filing requirements.

To utilize these limited exceptions, the taxpayer must have detailed knowledge about the tax profile of all direct and indirect owners of the PTE. In many cases, this information would prove to be difficult and costly to obtain, particularly in a tiered pass-through structure. It’s also important to note some PTE owners may need the information on Schedule K-3 to complete their return, specifically to claim a foreign tax credit. If a PTE relies on a filing exception, they may still be compelled to provide the schedule upon the owner's request. Finally, if a PTE does not file all required parts of Schedule K-2 and K-3 or reports incorrect information, the entity can be subject to penalties. Nevertheless, for those who do qualify, utilizing a Schedule K-2 and K-3 filing exception can save time, record keeping and compliance costs.

Taxpayers should work with their tax advisors, considering all relevant factors, when deciding whether to rely on a Schedule K-2 and K-3 filing exception.

Download the Tax Strategy Playbook for tax insights and opportunities that could impact your organization in 2024.

The information provided here is of a general nature and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any individual or entity. In specific circumstances, the services of a professional should be sought. Tax information, if any, contained in this communication was not intended or written to be used by any person for the purpose of avoiding penalties, nor should such information be construed as an opinion upon which any person may rely. The intended recipients of this communication and any attachments are not subject to any limitation on the disclosure of the tax treatment or tax structure of any transaction or matter that is the subject of this communication and any attachments. Baker Tilly US, LLP does not practice law, nor does it give legal advice, and makes no representations regarding questions of legal interpretation.