2024 Tax Strategy Playbook

Download the Tax Strategy Playbook for tax insights and opportunities that could impact your organization in 2024.

Baker Tilly’s inaugural Tax Strategy Playbook discusses the outlook for the new year’s tax policy landscape, outlines how current tax policy impacts your business and discusses opportunities for tax planning and mitigating inherent risks. We delve into various areas within federal, global and state and local tax.

Master federal tax for corporations: From maximizing net losses to excise tax and golden parachute planning. Your guide to critical tax strategies.

The tax treatment of distributions is of great importance to shareholders. Whether they’re treated as dividends, subject to a rate of up to 20% and possibly an additional 3.8% for the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT), or they’re a nontaxable return of capital, can make a substantial impact on a shareholder’s tax liability and return on investment.

The tax treatment of a distribution is determined by calculating the corporate entity’s earnings and profits (E&P). E&P is designed to be an economic measure of a corporation’s ability to pay distributions without distributing capital contributed by shareholders or creditors. It is a complex analysis with many adjustments that diverge from the traditional taxable income concepts.

E&P is determined on a separate entity basis annually from its inception and can be consolidated up to the parent corporation in a consolidated group. It can be a time-consuming effort for a corporation or consolidated group to compute E&P from inception if not performed annually. There can be significant penalties for not correctly reporting a distribution and for not distributing the appropriate amount of E&P.

E&P planning is a powerful tool that can allow for the avoidance of dividends, maximization of tax-free return of capital distributions, and movement with specific assets in certain tax-free transactions. Determining E&P and the taxability of distributions can be a complex task that should be undertaken annually to minimize tax liabilities.

Corporate taxpayers may find themselves in a taxable income position where they need to use net operating losses (NOLs) or other tax attributes (credits, etc.) to offset taxable income and reduce cash taxes. However, before these tax attributes are utilized, taxpayers should consider the impact of section 382 limitations.

Section 382 limits the use of NOLs or other tax attributes when there has been a shift of more than 50% of the ownership of a corporate entity within a testing period. A testing period is generally a rolling three-year window that restarts when there has been an ownership change. This provision was enacted to remove the incentive of acquiring a corporation with NOLs solely for the future utilization of those NOLs.

Once an ownership change has occurred, a section 382 limitation is calculated to determine the annual amount of NOLs and other tax attributes that can be used. This limitation is generally tied to the value of the company at the time of the ownership change and reflects an annual rate of return based on rates determined by the Department of the Treasury to allow for a limited amount of tax attributes to be used. The limitation also considers any unrealized built-in gains or losses at the ownership change date to adjust the limitation. Unused limitations can be carried over indefinitely to allow for future use of attributes.

Recently, in an effort to tackle runaway inflation, the Federal Reserve has instituted a tightening monetary policy, increasing the federal funds rate to their highest levels in two decades. This rise in rates has put pressure on the profitability of many operating companies. As a result, we expect NOLs and the ability to utilize them to become increasingly important.

It is highly recommended that a formal section 382 analysis is performed and updated on a regular basis if a company is planning to utilize NOLs or other attributes that may be subject to limitation. A section 382 study provides the clarity needed for effective tax planning; the study tracks the ownership changes over time, calculates any limitations, provides a rollout of the NOLs available by year, and can be used as a forecasting tool to determine cash tax that may be due in the future.

The qualified small business stock (QSBS) exclusion provisions were enacted to encourage investment in small business. The QSBS exclusion provides an opportunity for certain small business owners and investors to exclude gains on the sale or disposition of qualifying stock sales from federal income tax.

A qualified small business must be an active trade or business in a qualified trade or business (QTB). Generally, the provisions prohibit investment in certain service-related businesses including the fields of health, law, engineering, architecture, accounting, consulting and financial services, among others. In addition, the aggregate gross assets of such corporation at all times on or before the date of stock issuance may not exceed $50 million.

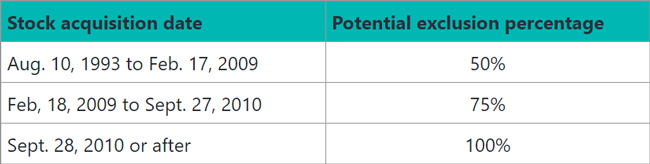

To be eligible for the exclusion, the shareholder must not be a corporation and must have received their stock as an original issuance directly from the eligible corporation. To be eligible for the full exclusion a taxpayer must hold the QSBS stock for a minimum of five years. The percentage a taxpayer can exclude depends on when the stock was acquired:

The amount of the exclusion is generally limited to the greater of $10 million or 10 times the shareholders’ tax basis in their shares of the QSBS that were disposed of, so the exclusion can represent a significant tax savings for eligible shareholders.

To the extent stock held that otherwise qualified for an exclusion, but do not meet the five-year holding period, a tax-free rollover option may be available allowing for a deferred recognition of the gain if certain criteria are met.

In the last few years, the QSBS exclusion has become a much more significant focus of small business investors. As such, the requirements must be closely reviewed before the investment, during the holding period and upon sale to ensure eligibility for the gain exclusion. Structuring alternatives may also be available in an acquisition scenario or in the restructuring current business operations to achieve QSBS eligibility.

Public companies repurchase outstanding shares of their corporate stock for a variety of reasons, including increasing earnings per share, reducing the cost of capital and consolidating ownership. While the use of excess capital to repurchase shares is often appealing to corporations and shareholders, the overall benefit of the repurchase may be reduced due to a new excise tax on share repurchases imposed by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

Effective in 2023, share repurchases by a “covered corporation” are subject to a nondeductible excise tax equal to 1% of the fair market value of any corporation stock repurchased during the taxable year. A “covered corporation” is defined as any domestic corporation whose stock is traded on an established securities market. The new provision does provide for exceptions to the excise tax for certain repurchases, which include repurchases that are part of a reorganization and a de minimis exception for net repurchases that do not exceed $1 million in a tax year, among others.

Though the proposal doesn’t seem to have any traction in the current Congress, it’s worth noting there is a proposal to increase the cost of the excise tax to 4% of the fair market value of stock repurchases. This recommendation was included in the Department of the Treasury’s General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2024 Revenue Proposals, or “Green Book,” which outlines the president’s revenue proposals. We’ll continue to monitor activity on the stock repurchase excise tax.

The implementation of the excise tax changes the math on the potential benefit of corporate stock repurchases. Corporations should evaluate the overall cost of repurchasing shares and be cognizant of the additional costs, transactions covered and exempted, due date of payments and financial statement reporting.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 created a new corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT) of 15% that took effect in 2023. Generally, corporations with average annual adjusted financial statement income in excess of $1 billion for three consecutive tax years are subject to the tax; these companies are referred to as “applicable corporations.” The CAMT calculates an alternative minimum tax at a flat 15% rate; the company’s ultimate tax liability is the greater of their CAMT calculation or their regular tax liability. For foreign parented groups, the threshold is a much lower $100 million.

Corporations subject to CAMT will need to calculate both their CAMT liability and their regular corporate tax liability to determine which is greater. For many large corporations, the corporate tax liability is extremely complex and nuanced. The CAMT will create the need for an additional intricate calculation based on an entirely different foundation — financial statement income, not taxable income.

Due to the $1 billion threshold, CAMT will only affect a small number of large corporations, but its implementation is expected to raise federal tax revenue significantly for the U.S. Treasury. While the corporate income tax rate is 21%, larger corporations have historically reported significant book income but have been able to take advantage of various tax deductions and strategies to pay minimal — and in numerous notable cases no — federal taxes. The creation of the CAMT was intended to improve overall fairness in taxation by ensuring the largest corporations contribute.

Companies should evaluate whether they may be subject to the new CAMT as these rather complex rules have taken effect. It is critical taxpayers are aware of the adjustments corporations are required to make, based on the guidance currently available, in calculating their adjusted financial statement income that could get the corporation over or under the $1 billion threshold. Once a corporation is an applicable corporation, it remains one, and is subject to the CAMT, for all future years.

For U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) financial statement reporting purposes, a company is required to identify and disclose deferred tax assets (DTAs) and deferred tax liabilities (DTLs). DTAs are essentially timing differences that may reduce tax in future periods; they result from net operating losses, credit carryovers and tax return timing differences. Once identified, the company must evaluate their ability to utilize DTAs to reduce future cash taxes paid. To be reflected on the balance sheet, DTAs must meet a “more likely than not” standard.

If the required standard cannot be met, a company must record a valuation allowance on DTAs, effectively reducing or eliminating those assets.

The analysis of whether a DTA meets the “more likely than not” standard is complex and requires a comprehensive look at the company’s future sources of income. Methods of income generation are specifically defined, and each must be considered. Tax planning strategies for this purpose are focused on generating future taxable income to allow for the utilization of DTAs. Any strategies devised must be prudent and feasible for the company to undertake.

The future income analysis must consider both positive and negative evidence, considering all relevant facts to determine if a position is supportable. Examples of evidence may include history of earnings, reliability of projections, sales backlog or expiring tax losses.

The process of evaluating DTAs is required as of each balance sheet date. Financial statement auditors evaluate this judgment and conclude whether a company’s position appears reasonable. It is a best practice for a company to evaluate and document their DTA positions with a knowledgeable tax advisor prior to a financial statement audit to make the audit efficient and ensure all are comfortable with the judgments made. The value of quality financial statements to stakeholders cannot be overstated.

When considering whether the income tax expense reported on a profit and loss statement (P&L) is reasonable, the effective tax rate reconciliation is a key item to review. A company’s effective tax rate (ETR) is calculated by dividing income tax expense by continuing operations income before income tax expense. A reconciliation of the ETR is a required disclosure for public companies but optional for private companies. While an optional disclosure for private companies, it is a useful tool in evaluating a company’s financial position and highly recommended to be part of a private company’s provision support files.

The ETR reconciliation shows drivers of income tax for the organization, such as state taxes, foreign taxes, tax credits and nondeductible expenses or other permanent differences. Evaluation of the adjustments shown on an ETR reconciliation provide insight, especially when compared with previous years, to show trends driving tax rates and highlight variations that should be considered. ETR results can also be compared to public competitors, which can help companies understand their own tax outcomes and consider planning opportunities.

While typically helpful, there are times when an ETR reconciliation can be misleading or challenging to interpret. This can happen if the company has a valuation allowance or when the company’s income is at or close to break-even. Since the ETR is calculated by dividing tax expense by pre-tax income, a lower denominator can impact the appearance of the results making the resulting reconciliation less intuitive.

Soon, all companies will be subject to increased reporting requirements, some of which will impact the calculation and presentation of ETRs. Late in 2023, the Financial Accounting Standards Board issued new guidance requiring a detailed breakdown of taxes by federal, state and foreign jurisdictions. These requirements will make rate reconciliations more cumbersome, while providing more decision-useful information about a company’s income taxes. Public companies will need to comply with the guidance for annual periods beginning after Dec. 15, 2024, while private companies will have an additional year to adopt. Early adoption is permitted.

ETR reconciliations are critical snapshots of tax positions and a great tool for discussion and learning about the tax drivers of the organization. We recommend all companies perform and examine the results of an ETR study annually with an experienced tax advisor.

For a “certain” tax position to be recorded for financial reporting purposes, that tax position must meet the standard of “more likely than not” (MLTN). Companies must have a sufficient understanding of tax positions to be comfortable making assertions they are reaching this standard.

While it’s preferential to take certain tax positions that meet the MLTN standard, sometimes companies choose to take positions on their return that do not meet this level of authority, leading to uncertain tax positions. For any uncertain tax position taken, a reserve for the tax benefit of such position must be recorded in the financial statements. Uncertain tax positions carry inherent risk; company management should work with their tax advisor on quantifying this risk and assess their risk tolerance before taking an uncertain tax position.

Financial statement auditors are required to evaluate this judgment and conclude a company’s tax position appears reasonable. Proactively assessing positions and documenting conclusions made will assist with a company’s audit.

Reaching the conclusion that a tax return position meets the more likely than not standard requires a facts-and-circumstances analysis based on “unit of account” and the company’s individual situation. To aid in making these determinations, there are several practical items a company should consistently share with their internal tax team and external tax advisors, including:

With robust discussion of these matters and regular communication, a knowledgeable tax advisor can support the evaluation of uncertain tax positions and ensure that processes are complete to thoroughly assess and document their conclusions.

Corporations anticipating a change in control should be aware of the potential tax implications for upcoming payments made to certain executives. For employers caught unaware, this often results in a situation that can become costly and delay a transaction from closing.

This tax provision, known as Internal Revenue Code (IRC) section 280G, applies to C corporations and pertains to certain compensation paid to executives that are related to a change in control of the corporation, which are referred to as “parachute payments.” In the event a parachute payment is considered “excess,” the payment is subject to a 20% excise tax (paid by the executive) and the employer is disallowed a deduction for the excess payment.

Fortunately, there are avenues for relief to eliminate exposure to these negative tax outcomes. One such strategy, available only to private companies, is to conduct shareholder vote. However, this approach is not without complication; executives must put their rights to the payment at risk, there are optic concerns stemming from disclosure requirements and the vote requires approval from more than 75% of all shareholders.

While this can be a useful strategy, given the complex and delicate nature of the requirements, blind reliance on the shareholder vote to cure the excise tax exposure is not advised.

The best strategy to ensure golden parachute payments do not derail a transaction is proper planning. For those anticipating a transaction, a preliminary golden parachute analysis to determine exposure is highly recommended. Once exposure is quantified, it may be possible to reduce the exposure, if not eliminate it, before it becomes a problem. Although a transaction may not be on the horizon currently, it is never too early to start the planning process to be prepared.

As the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) continues to review the work of audit firms, Internal Controls over Financial Reporting (ICFR) remain at the top of the priority list and a primary source of audit deficiencies. ICFR audits assess the risk in a company’s internal processes and controls over information presented in the financial statements. Common audit deficiencies related to testing ICFR include:

Increased PCAOB audit deficiencies could create new issues for you and your tax team, including longer audits, more required documentation and increased scrutiny over procedures performed. Companies are not able to rely on past audit history, as a more stringent quality review may bring up additional questions or request additional support not previously required.

When a company has audit deficiencies, the tax department continues to experience the burden of internal pressure to improve accuracy, transparency and efficiency, on top of the complex nature of Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 740 tax processes in general. These deficiencies create a ripple effect of increased burdens to meet new, more stringent requirements.

Performing a periodic review of your tax processes and controls will help companies avoid this outcome. A knowledgeable tax advisor can assist with:

Download the Tax Strategy Playbook for tax insights and opportunities that could impact your organization in 2024.

The information provided here is of a general nature and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any individual or entity. In specific circumstances, the services of a professional should be sought. Tax information, if any, contained in this communication was not intended or written to be used by any person for the purpose of avoiding penalties, nor should such information be construed as an opinion upon which any person may rely. The intended recipients of this communication and any attachments are not subject to any limitation on the disclosure of the tax treatment or tax structure of any transaction or matter that is the subject of this communication and any attachments. Baker Tilly US, LLP does not practice law, nor does it give legal advice, and makes no representations regarding questions of legal interpretation.